Geographical parameters and temporal framing are the factors of categorizing each architectural style. However, in the vastness of the Saudi Kingdom, it might be more adequate to limit the study on a comparative spatial illustration, and refrain from the historical and architectural narratives. Thus, it would be a straightforward approach to mosques characterization for several millennia, since the birth of Muhammad’s (PBUH) divine message; as the springboard of Mosque Architecture. No question, the first Mosque Form style is that of the Prophet (PBUH), for its exemplar influence on the mosques of the Arabian Peninsula in terms of their modesty, minority and compatibility with its surrounding built environment free of extravagant ornaments. From this event on wards, the Prophet Mosque has been the Mosque Form guidance model.

Undoubtedly, this illustrative study necessitates a clear-cut developed field survey methodology, on which mosques would be categorized according to their geographical allocations. Each allocation has developed its own character by virtue of its specific cultural setting, weather condition, topographical status, technical factors and available local materials right there. Yet, all mosques had sustained modesty and simplicity abiding by their pioneering role model in Medina. The Urban Heritage Center of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage SCTH delegated by the Historic Mosques Program has carried out a number of preliminary surveys of mosques all over the Kingdom. Hereby, the author postulates his study based on surveying 1300 Historic Mosques including an expository architectural documentary in the framework of their geographical allocation, cultural background, climatic conditions and construction strategies.

- Hijazi Style:

- Located in Mecca, Medina, Taif and Jeddah.

- Uses variant building materials; coral stone in Jeddah, clay in the rest of the cities.

- Characterized by their mutual facades stitched with Rowshans and Mashrabiyas.

Mimar Mosque – Jeddah

- Red Sea Coast Style

- Located in Yanbu, Duba and Southern Jeddah.

- Characterized by Rowshans.

- Similar to the Hijazi Style but for minor details.

Sonousi Mosque – Yunbo

- Tuhami Style:

- Located in Tihama villages on the outskirts of Taif reaching Jizan.

- Characterized by its multi-floored stone constructions, meanwhile straw and branches (Arayesh) are used in Jizan.

Abdullah Bin Abbas Mosque – Taif

- Sarat Mountains Style:

- Located in mountain zones; Asir, Jizan, Bahah and Taif.

- Characterized by stone constructions; as the Tuhami Style yet distinguished for its stone types.

Al-Koua Mosque – Taif

- Southern Desert Style:

- Located in Dhahran Aljanoub and Najran.

- Characterized by multi-floored clay constructions.

Alhouza Mosque – Dhahran Aljanoub

- Asiri Style (Rain Shades)

- Located in Abha and its sidelines.

- Characterized by horizontal shelf-like stone-coated clay all over its facades, to get protected from the drifting rains.

Historical Tabab Center Mosque – (Aasir) Abha

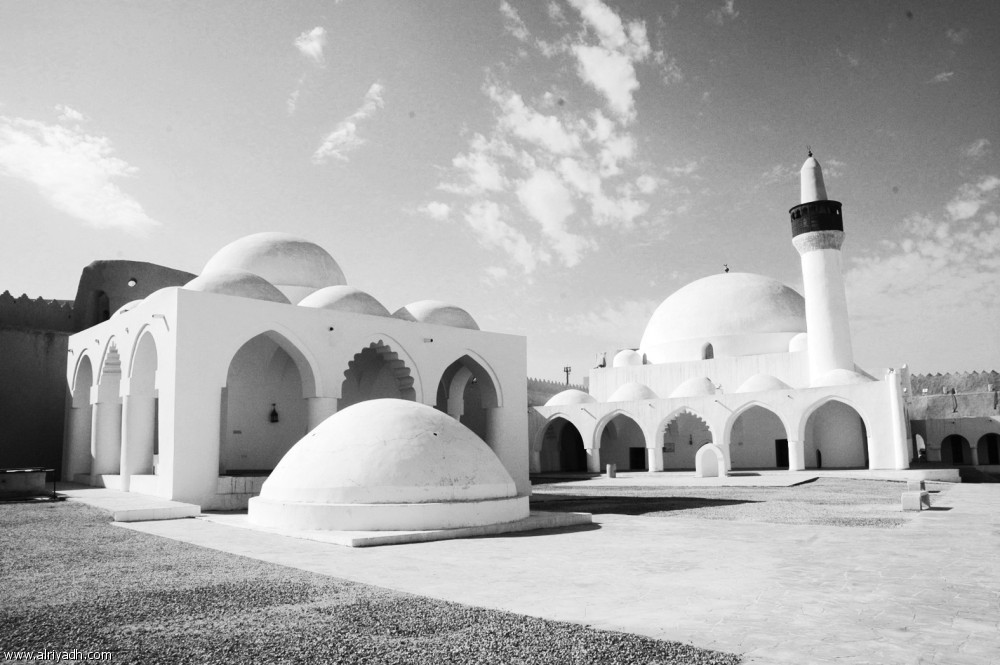

- Najdi Style:

- Located in Riyadh, Qussaim and Ha’il.

- Characterized by its distinguished visual features, and the use of clay.

- In Ha’il, clay may be mixed with coral stones spread by the scattering sediments right there.

Al-Dwaihra Mosque – Diriyah

- Al Ahsaa Style:

- Located in Al Ahsaa and the Eastern Coast region.

- Characterized by its decorative visual features using clay and limestone.

Alfoqi Mosque – (Aasir) Abha

- Arabian Gulf Style:

- Located in Qatif, Aljubail, Dammam and Khobar.

- Similar to the prevalent styles along the gulf.

- Characterized by using sea stones (Farouch) and limestone.

- Northern Style:

- Located in Tabuk and Jawf.

- Characterized by using both clay and stone.

Umar Ibn Al Khattab Mosque – Dumat Al Jandal

This Architectural Style typology is just a preliminary attempt to categorize mosques within the kingdom and display its vernacular architecture. This categorization is liable to get developed in the future. Thus, it is necessary to conduct a thorough study regarding the development of Mosque Architecture in the fourteen late centuries in the light of this typology. In general, Historic Mosques must be addressed in their variation from former to latter though being in line, especially that the first survey encompasses Mosque Forms since the birth of Islam till the first half of the twentieth century. It is believed that mosques of this era had been rebuild several times adding slight changes to the original construction.

A Comparative Historic Mosque Factors Illustration

It is worth-noting that these cardinal mosque factors have signalized Mosque Architecture all over the Arabian Peninsula till now; as in the trellises covering the parallel section to the kiblah wall, which is open to the courtyard. Likewise, Al Saffa, which is another trellis at the end of the mosque. Sometimes, this Saffa functions as a hall enclosing the courtyard within. These mosques had been voided of minarets, domes, minbar(s) and mihrab(s), where the last had been tokened by place. Accordingly, it is assumed that there have not been any major changes to the Historic Mosque structure. Hereby, a comparative Historic Mosque factors study would be displayed in terms of the elucidated style typology.

Urban Block in Context

Historic mosques are marked with their interweaving with their urban context but for seldom cases. Usually, these mosques act as the central nucleus of their urban gatherings; as witnessed in Al khbraa in Qussaim and all over the Southern and Northern regions of the kingdom. However, the case is somehow different in larger cities, for mosques come in hierarchal cluster order. There, a central main mosque is allocated for Jumaa’ prayers among other subsidiary smaller lane mosques for the daily ritual five prayers. Yet, sometimes lane mosques act as Jumaa’ central ones; each in its lane surrounded by their smaller counterparts in those cities of abundance of lanes. Each serves its urban gathering. For instance, Hofuf town in AI Ahsaa lying in the Eastern region homes several Jumaa’ lane mosques; Al Jabri in Al Kut district and Imam Faisal bin Turky in Al Ta’athul district. Furthermore, Shafe’i and Mi’mar mosques in Jeddah are distinguished with their coherent interweaving with their urban context, where they are not easily detected but for their minarets.

Shafe’i Mosques – Jeddah

This inclination has been dominant in Historic Mosques, since the construction of the Prophet Mosque in Medina till the beginning of the Ottoman Caliphate. Henceforth, this course had been dethroned by the start of the seventeenth century. A dome has been added to the mosque Form; as in Ali Pasha mosque in Al-Ahsaa with Seljuk Anatolian touch. Contrary to its formers, mosques have been desolated from their urban context. The mosque has been allocated within the Al Ahsaa governing campus (Ibrahim’s Palace). This applies to many of the mosques built in Hijaz in Medina, even in Mecca and other sanctuaries. In the twentieth century, AL-Anbariya mosque has been founded by the Hijaz railway in Medina.

AL-Anbariya Mosque – Medina

In conclusion, It is acknowledged that historic mosques; as urban blocks; in the Kingdom had always been interweaving with the other neighboring blocks. They could not be pinpointed neither by sky nor height. Still, many of them used minarets as landmarks in their urban context. This had not been always the case for those mosques in the Southern region of the Kingdom for they had no minarets. Thusly, mosques simplicity and integrity did not stand beyond outlining the “sky line” in most of the old towns.

Prayer Hall

The trellis prayer hall had not been validated, to comply with the climatic and technical turnovers, adapting various forms according to the spatial and temporal contexts. In most of Najd, Al Ahsaa and Dumat Al Jandal in the North, Historic Mosques, were of columned singular or double-row front trellis open to the courtyard. This style had been domineering in the great Islamic cities; Cairo, Bagdad and Damascus but larger in size and more complex in spatial and technical respects. On the other side, mosques in the Kingdom did not part with their former modesty, to sustain its distinguished form adding pointed clay spoila as in Najd, and halfcircled plaster-coated clay stone ones as in Al Ahsaa. Examples can be seen at Al Sariah Mosque and Umar Mosque in Diriyah neighborhood in Dumat Al Jandal.

Al Sariah Mosque – Diriyah

Most of the Tuhami and Jubaili mosques are fully fortressed from the courtyard, to stay away from the cold weather, whereas, the Hijazi style had undertaken astounding changes to resemble the great mosques nowadays; as in Shafe’I and Mi’mar mosques. By the Ottoman conquest expansion towards the Eastern region, some Ottoman traits had shown on mosques; as in Ali Pasha mosque and The Dome mosque, where the latter has revolutionized the use of domes with a prayer hall void of columns. The mosque has survived till the time being, meanwhile using burnt bricks has vanished by the evacuation of the Ottomans.

Ali Basha Mosque (Al-qouba) – Al-Hofuf

Halls and Courtyards

These are the main assets of Mosque Aarchitecture till the time being, for it has been the extension of the Prophet’s Mosque. Yet, these factors have been subordinated in the Asiri, Tuhami and Jubaili mosques, where mosques look on to the courtyard of the town homing the prayers’ gathering after each prayer and hosting the arriving visitors to the town. This area has been of multi-functional uses. Fortunately, these halls have been sustained in Najd and Al Ahsaa validating their early originality and simplicity. Additionally, the Prophet’s Mosque Saffa has been incarnated in the hall-enclosed courtyard. This form has not been notably developed in these areas, but for Al Jabri Mosque in Kut district, Al-Hofuf in Al Ahsaa. In Hijaz and Najd, there was found more than 600 courtyards dating back to the construction of several mosques for Hijaz has eternalized most of the developmental styles taking place in the Great Islamic countries.

The prayer hall with the central dome was built conditioning a courtyard, but it has a hallway in front of the closed prayer hall, which is contrary to the style of the mosques that had been existent 450 years before in the region. This is found in the Anbari mosque in Medina in its Ottoman style at the turn of the twentieth century. It is emphasized that exceptions in the construction of historical mosques in the Kingdom does not represent the basic architectural elements, which endows the uniqueness that has always been associated with the construction of the mosque.

Ali Basha Mosque (Al-qouba) – Al-Hofuf

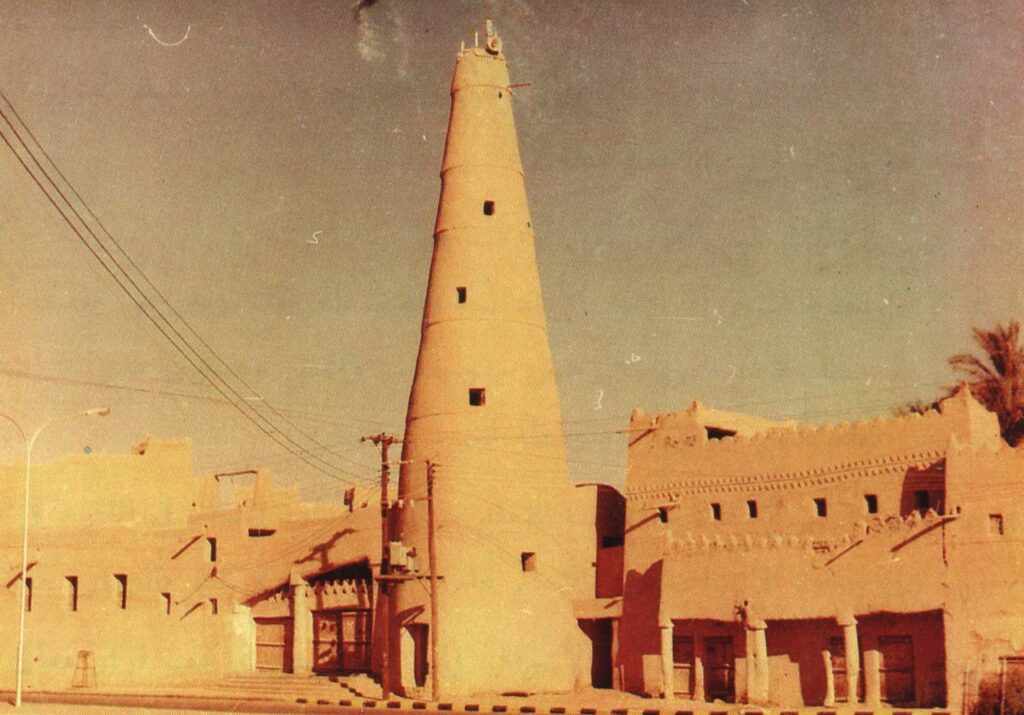

Minarets

Minarets are novice Mosque Architecture factor for they have been introduced by the Umayyads in the early years of the first Hijri century by the construction of The Umayyad Mosque. This novice idea had been foreshadowed, when the crier of the prophet mounted the loft on the roof of the mosque to call for the five prayers. This loft had been sustained in Najd, Jubaili and Asiri mosques rather than the minaret, in spite of taking to the multi-floored houses in these areas. Minarets knew no development till mid the twentieth century. The earliest minaret in the kingdom has been detected in Umar Ibn Al Khattab Mosque. Well, I could not figure out the exact date, but it resembles that pyramidal graded one in Kairuan of Uqba Ibn Nafe’ Mosque.

Umar Ibn Al Khattab Mosque – Dumat Al Jandal

In Najd, minarets are mostly cylindrical or beveled funnel shape, and it may be of quad lateral base. These minarets are usually allocated above the prayer hall with a staircase attached to it. Some of them went farther, divided into rooms for performing Tahajud prayers in Ramadan as in Aniza in Al Qussaim. Minarets have been the distinguishing mosque factors in Najd, while in Al Ahsaa minarets have reached an epic privacy level for their limited heights and domed cylindrical minarets. Other Seljuk minarets were funnel shaped with pointed or domed heads surrounded by protruding wooden engraved porches. As for Hijaz, there are multifarious minaret forms, yet influenced by the Ottomans and Mumluks.

Unaizah Mosque – Qussaim

The need to raise the minaret was limited because most of the urban settlements were small and did not expand much even in large cities such as Mecca Medina, Hofuf and Jeddah, and the need for large elevations remained very limited to specific areas that may be in Sudair and Qussaim. The reason for the rise of minarets in Najd villages is that it was used as a controlling tower. The area is famous for such towers as the AlShananah tower in Qussaim. That the mosques where there are no minarets, as in the southern regions of the Kingdom are originally limited family gatherings so there was no actual need for the minaret. In fact, if we look carefully and try to link the evolution of many elements in the mosque with social culture and topographical and climatic features, we will see many characteristics of the styles of historical mosque architecture in the Kingdom.

AlShananah Tower – Qussaim

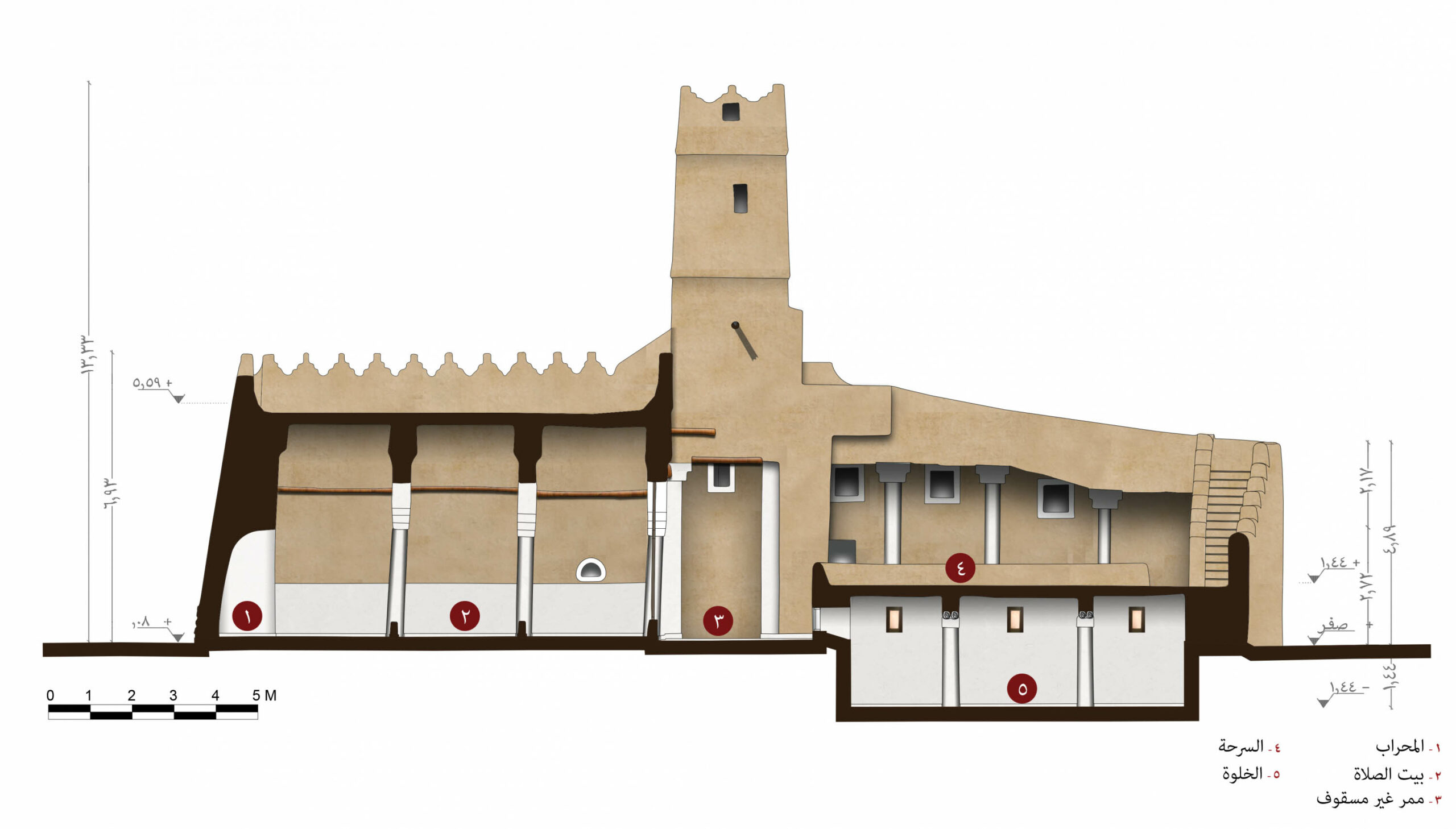

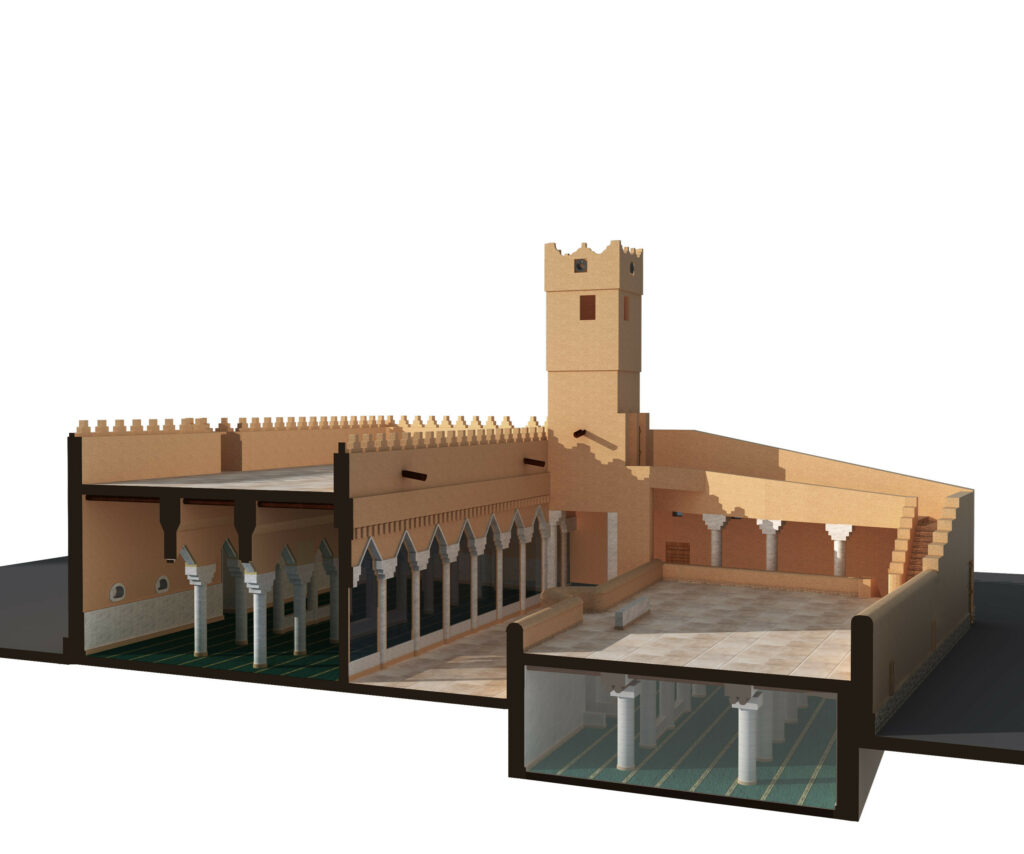

Hermitage and Other Factors

Historic Mosques have been always compliant with their context weather conditions; moreover, they have been in continuous development to meet the peoples’ needs in the four seasons of the year. In Sumner, the prayer hall is often opened to the courtyard as in Najd, Al Ahsaa and the North of the Kingdom from noon to afternoon. Whereas, prayers have used to perform their sunset, evening and dawn prayers in the hall or the roof of the mosque, especially in Najd. Therefore, there have been staircases to the roof of the prayer halls in most of the Najdi mosques. Other mosques consisted of mihrab within the hall as an alternative to that one in the prayer hall. In winter, there have been underground hermitages as prayer halls linked to the hall by a staircase. It had been either used for night prayers or all of them according to the weather condition.

It is worth mentioning that people in Najd were aware of its topography. In Jaljil; a Najdi suburb, there had not been any underground hermitage; as the whole town was floating on water stream. Al Dhuhaira mosque in Diriyah, the hermitage had been allocated above the hall. The hall had been divided into two sections; on the same level of the prayer hall, slightly elevated one for the land topography was not compatible with an underground hermitage. Prayer places had been of adaptable flexibility and mobility achieving functionality. That was the driving force for the motivation to sustain this flexibility.

Al-Dwaihra Mosque – Diriyah

Al-Dwaihra Mosque – Diriyah

Ablution closets were alike. It was all about a water well, where water is lifted from it into an exposed open waterway reaching terminal openings that are controlled by the wall separated users for privacy concerns. There is a watercourse in the ground to drain the water of ablution ‘to the so-called “spring” to collect this water. It is rare, for example, that this water is used for agriculture, but sometimes there is something like the small garden adjacent to the mosque called Al Ahsaa “Bustan”. The organization of the spaces and functional elements of the places of ablution are simple and practical and economic. It had not been developed like the great mosques in Islamic cities to become fountains and routes but remained simple and useful with some rare exceptions.

Decorative Elements

In general, Historical Mosques are not ornamented, but for rare cases, which decorated with frescoes and engraved wooden doors. These had been functional ornaments; such as the “quwat” walls or “Rowazin” as called in Al Ahsaa. These have been used as protective wall mount storage units for Koran and other religious books or preserving the night light bulbs. The use of spoilas can be seen in the opposite wall of the mosque, which sets the beginning of the prayer hall. Each area had its own style which can be distinguished from its counterparts.

“Quwat” or “Rowazin”

As for the use of domes in the Historic Mosques had been for rare cases lately. It had been innovated by the Ottoman Caliphate in Hofuf. There are small domes as in Al-Jabri mosque in Al-Ahsaa as a structural additive rather than aesthetic element. The late Hijaz mosques in the Ottoman reign are characterized by domes such as in the Prophet’s Mosque and other mosques spread throughout the region, with their absence completely in the rest of the regions. I would like to refer here to the characterization of the Historic Mosques in the Kingdom and their originality in spite of the mentioned exceptions.

Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) Mosque – Medina

Conclusion

A worth noting remark is that Historic Mosques in the Kingdom has demonstrated the uniformity of the dynamic axis pointing out the mihrab, which had not been survived in large cities. Any architectural development attempt had been originality oriented for functional purposes serving the users’ needs and considering their limited resources. This reflects the lagging development of old towns and cities for mosques to be the motion center but has always been an extended part of the urban and its dynamism to be simple, spontaneous and functional rather than aesthetic.

It is a brief demonstration to unveil the variant architectural styles typology of Historic Mosques in the Kingdom, influenced by the topography, geography and culture to maintain their coherent conformity to the early mosques generation in the region, adapting the same factors, yet developing several national identities. From my own perspective, these mosques must be profiled in terms of their sequential historical narratives and developing architectural forms from one geographical parameter to another and the subsequent influences, which had resulted in the supreme uniqueness of Mosque Forms.